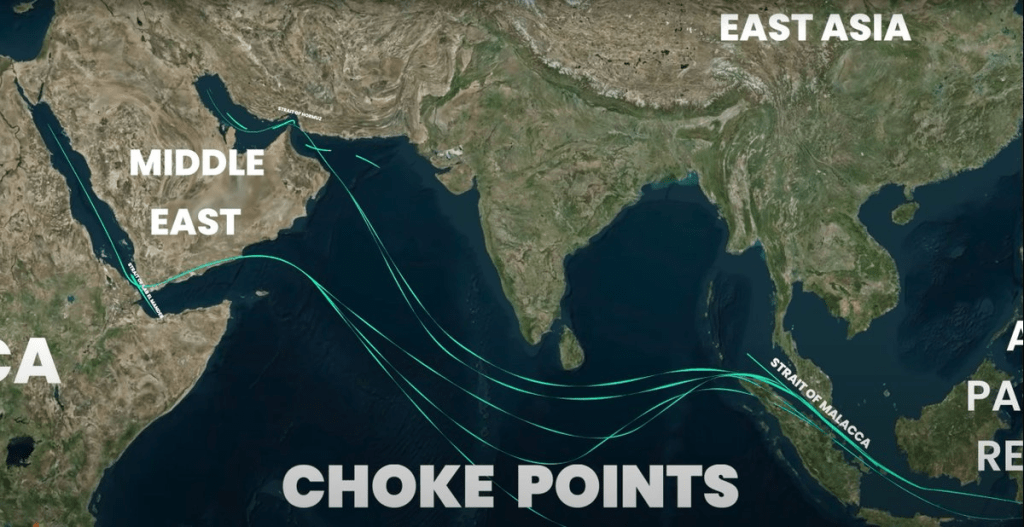

Hace una década escribí un paper sobre el Estrecho de Malaca y su rol como uno de los espacios geopolíticos más críticos para el comercio y la seguridad energética. En aquel momento el argumento podía sonar “técnico”: rutas marítimas, volúmenes, piratería, riesgo, dependencia de importaciones. Hoy, con la reactivación de los conflictos armados en Asia Occidental (aka. Medio Oriente) y la tensión directa sobre el Estrecho de Ormuz, esa tesis ya no se lee como un ejercicio académico sino como un recordatorio para interpretar el presente.

Lo que está en juego una vez más no es solo “un estrecho más” en el mapa. Es la arquitectura física de la economía global: las redes logísticas dependen de pasos geográficos estrechos y que, cuando uno se vuelve incierto, el costo se propaga a toda la cadena (energía, fletes, seguros, insumos industriales, alimentos e inflación globalizada).

La globalización no flota: se “atasca” en lugares muy concretos

En el paper sobre Malaca sostuve una idea simple: los flujos globales tienen puntos de paso obligados. El comercio marítimo se concentra porque el planeta (y la ingeniería portuaria) no permiten infinitas alternativas y porque el transporte terrestre sigue siendo aún muy caro. Por eso, un cuello de botella puede convertirse en palanca estratégica y herramienta de política económica.

Esta lógica aparece también en análisis contemporáneos de seguridad marítima: los estrechos no son “accidentes geográficos”; son nodos estratégicos dentro de un sistema interdependiente donde el tránsito comercial, el poder naval y el control marítimo se superponen. Un informe del Hague Centre for Strategic Studies lo sintetiza con claridad: en los extremos del Océano Índico se ubican dos de los cuellos de botella más relevantes de la actualidad: los Estrechos de Malaca y Ormuz. El cuello de botella del Estrecho de Malaca es en su punto más angosto de tan solo 38 kilómetros. y el del Estrecho de Ormuz es de 33 kilómetros.

Malaca: el corredor que conecta el taller del mundo

Malaca es el corredor que vincula el Océano Índico con el Pacífico y la vía hacia y desde las cadenas de valor que alimentan a Asia oriental. En mi texto destaqué por qué, para China, la dependencia de ese paso se vuelve un problema estructural: el estrecho concentra tránsito, está expuesto a disrupciones y obliga a pensar en rutas alternativas (oleoductos, corredores terrestres costosos, diversificación de puertos y préstamos a países en la región, entre otros).

Esa idea tiene eco en literatura geopolítica más amplia. especialistas como Will Rogers del Centro para una Nueva Seguridad Estadounidense o Roger Kaplan en el libro la Venganza de la Geografía, usan Malaca como ejemplo de geografía que condiciona la estrategia: un paso “estrecho y vulnerable” cuya relevancia crece en una continuidad que enlaza el Indo-Pacífico con Medio Oriente. Y junto a ellos, desde el campo de estrategia marítima, Geoffrey Till en el libro Poder naval: una guía para el siglo XXI insiste en que el mar no es un “vacío”: es infraestructura de poder y comercio; las rutas marítimas y sus restricciones geográficas se vuelven determinantes para la proyección económica y política.

Ormuz: la válvula del sistema energético global

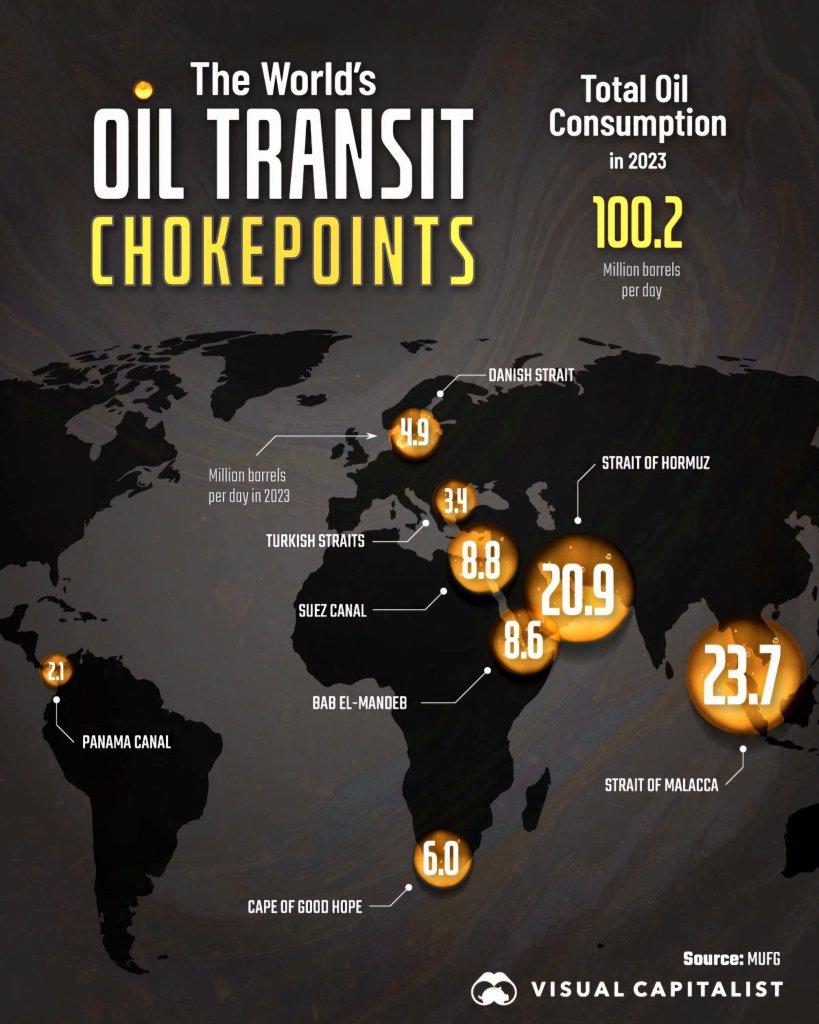

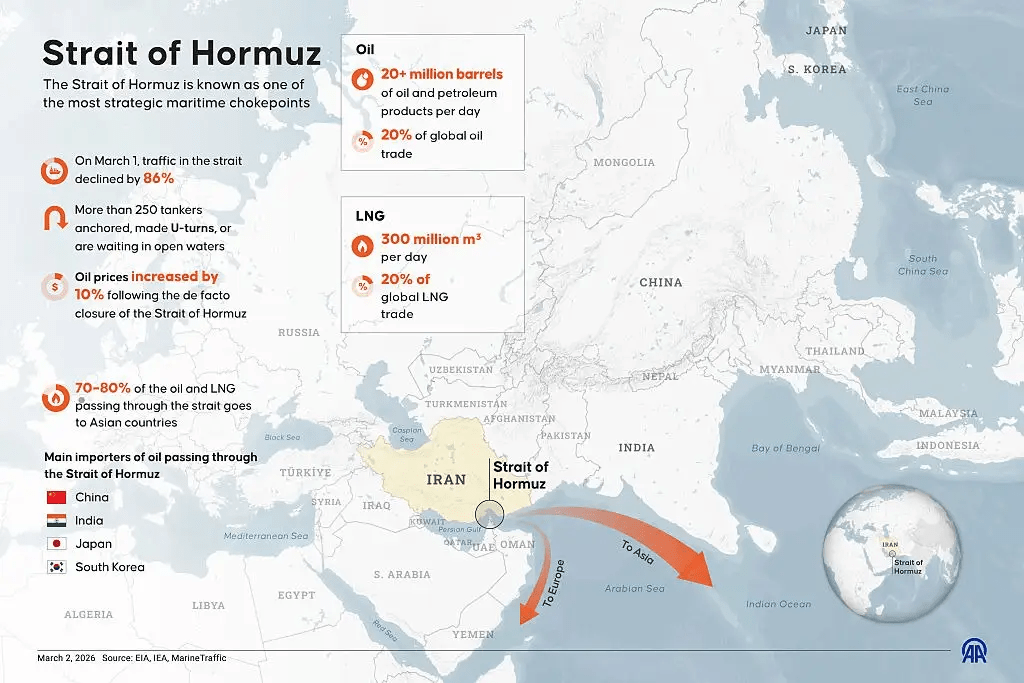

Si Malaca es el corredor del comercio Asia–mundo, Ormuz es la válvula del Golfo Pérsico y de toda Asia Occidental hacia el mercado global. La U.S. Energy Information Administration estima que por Ormuz transitan del orden de ~20 millones de barriles por día (aprox. una quinta parte del consumo mundial de líquidos petroleros), además de flujos relevantes de gas natural licuado. Visual Capitalist en la siguiente gráfica confirma que, de los 100 millones que barriles que consume el mundo diariamemente, el 20.9% transita por el Estrecho de Ormuz (casi tanto como el que transita por Malaca -23.7%-):

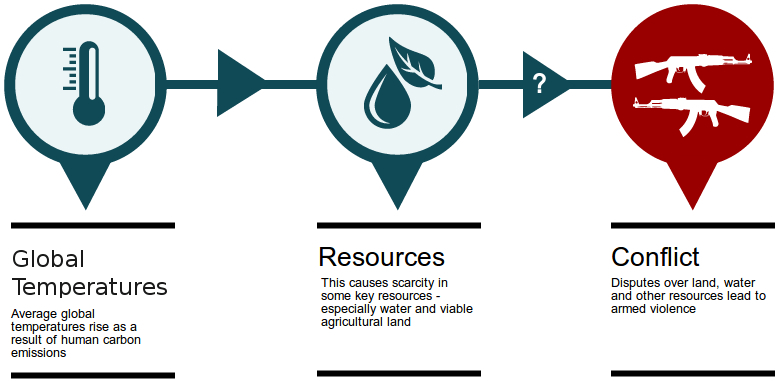

Esa centralidad explica por qué, cuando Ormuz entra en zona de riesgo, la economía global reacciona con la lógica de “prima de guerra”: no hace falta que falte petróleo o gas físicamente para que suba el precio; basta que aumente la probabilidad de interrupción, que suba el costo de los seguros, que haya desvíos y que el tiempo de tránsito se dispare.

La coyuntura actual: conflicto armado y disrupción logística

Las noticias más recientes describen un deterioro rápido de la situación: advertencias y ataques a buques, tráfico reducido, envíos varados, incrementos en los costos de flete y de cobertura de riesgo en aumento de precios. Reuters reportó la preocupación oficial del sector naviero griego ante una situación “alarmante” y la recomendación de evitar la zona mientras que los precios en toda Europa y Asia se fueron al alza. AP ha documentado disrupciones que se extienden más allá del petróleo (manufacturas y carga en general, farmacéuticos, electrónicos, derivados petroquímicos, alimentos, entre otros), con acumulación de buques varados y sobrecostos logísticos. Otros medios de comunicación, señalan ya alzas fuertes en crudo y gas por el impacto del conflicto en producción y tránsito marítimo.

Asimismo, el bloqueo potencial del Estrecho de Ormuz por mucho tiempo pondría en riesgo la existencia misma de los países del Consejo de Cooperación del Golfo (GCC, por sus siglas en inglés) que importan la mayor parte de sus alimentos y agua por esa vía. En promedio, los países del GCC importan alrededor de 85% de sus necesidades alimentarias y una parte relevante de esos granos y básicos entra por rutas que dependen de chokepoints; por ejemplo, estimaciones académicas y de centros especializados indican que ~35% de importaciones de trigo y granos forrajeros del GCC pasan por Ormuz, y que ~81% del arroz importado se embarca por esa vía. En la coyuntura actual, esto importa porque el “shock” no se limita al crudo: cuando sube el riesgo (seguros, desvíos, demoras), se encarece y se vuelve más frágil la logística de alimentos hacia puertos hub del Golfo.

En agua, el vínculo es más indirecto pero potencialmente más crítico porque la seguridad hídrica del Golfo depende masivamente de la desalinización, y varios países obtienen una proporción muy alta de su agua potable de plantas costeras (p.ej., se citan cifras del orden de ~70% en Arabia Saudita, ~90% en Kuwait, y valores altos también en Omán y EAU). Esas plantas son infraestructura costera (tomas de agua, energía, químicos, repuestos y mantenimiento) y, en un escenario de escalamiento, el riesgo no es que “el agua pase por el estrecho” como un cargamento, sino que el conflicto armado, las bombas a plantas de desalinización y la disrupción marítima eleven la vulnerabilidad del sistema. Cualquiera de esats acciones empezará a causar no solo interrupciones en insumos industriales, en cadenas de mantenimiento, en energía, o daños/amenazas a instalaciones costeras pueden traducirse en estrés hídrico rápido sino también en motivos para que la población opositora a los regímenes sunnies aumente. La idea de tan alta dependencia del ingreso de agua y alimentos a la región es un claro ejemplo de altísima dependencia de alimentos y agua y una alta dependencia de desalinización.

En términos de impactos de “red”, el fenómeno es claro:

- El nodo se vuelve incierto → navieras y cargadores empiezan a reaccionan.

- Sube el costo del riesgo (seguros de riesgo, sobrecostos en claúsulas de riesgos de guerra y otras cláusulas y recargos vinculados) → se encarece el flete.

- Se desvían rutas (por ejemplo, rodear el sur de África) → aumentan días o semanas, incrementa uso de combustible, aumenta la congestión portuaria.

- Se recalculan inventarios (“just-in-time” deja de funcionar) → inflación importada y tensión productiva aumenta.

Por qué estos estrechos revelan la desigualdad real de la economía mundial

Hay una lectura incómoda que se vuelve evidente cuando comparas Malaca y Ormuz: la interdependencia es asimétrica. Los costos del shock no se distribuyen “parejo” y algunos pagan la facturas:

- Quienes controlan el financiamiento, los seguros, las certificaciones, los puertos hub y las navieras suelen trasladar costos “río abajo” al consumidor final y a los países del sur global.

- Economías importadoras de energía o exportadoras de bajo margen, son las que tienden a absorber el golpe vía inflación, deterioro de términos de intercambio y presión fiscal.

- Muchos países quedan atrapados entre dos realidades: necesitan insumos de los mercados globales, pero no controlan ni las reglas ni los puntos físicos por donde pasa la circulación.

Esto conecta directamente con el argumento que yo había planteado con Malaca: el “estrangulamiento” no es solo militar; es poder sobre la circulación. Un chokepoint permite influir en precios, tiempos y viabilidad de rutas. Y por eso, en épocas de crisis, el mapa manda: los discursos de “mercados fluidos” se subordinan a geografía, logística, riesgo y coerción.

Dicho de otra forma: la red global existe, pero no como simetría. Existe como una distribución desigual de control sobre la circulación y de capacidad de comprar resiliencia.

¿Existen alternativas? Sí, pero nunca equivalentes

En el paper yo resaltaba la respuesta típica ante Malaca: buscar bypasses (corredores terrestres, oleoductos, diversificación) y reducir dependencia. Como hemos visto en los últimos 10 años desde ese paper, la billonaria inversión que China ha hecho en la Ruta terrestre de la Seda no se da abasto para siquiera acercarse a funcionar como un bypass. Tan solo en la última década, la inversión acumulada de la RPdeChina bajo la Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta (Ruta de la Seda) se estimaba en el orden de US$1.0–1.2 billones de 2013 a 2023, combinando contratos de construcción e inversión no financiera (con desglose aproximado de US$634 mil millones en construcción y US$419 mil millones en inversión e). Aun así,este monto no “reemplaza” Malaca ni el transporte marítimo porque el mar sigue siendo, por física y economía, el modo más barato y masivo para mover contenedores y graneles: los corredores terrestres (ferrocarril/carretera) tienen capacidad mucho menor, más fricciones fronterizas y regulatorias, costos logísticos más altos para cargas pesadas/voluminosas y a menudo requieren transbordos (tren–camión–tren) que reducen la eficiencia; además, gran parte del comercio Asia-Europa y Asia-Oriente Medio depende de una red portuaria y naviera ya instalada, con economías de escala difíciles de igualar.

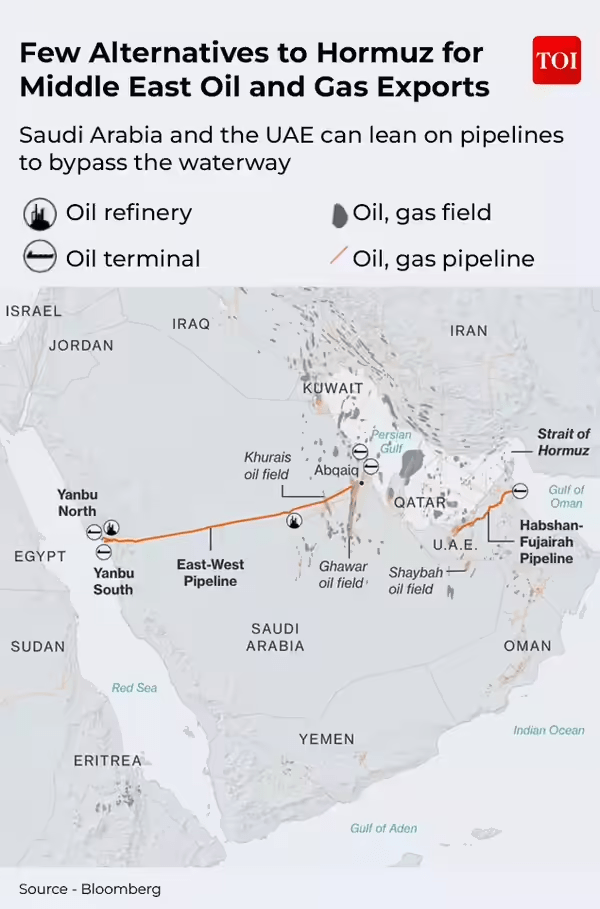

Ormuz muestra lo mismo: existen opciones parciales en la Península Arábiga o hacia el norte de Asia Occidental (terminales fuera del estrecho, oleoductos hacia otras costas) pero tienen capacidad limitada y no reemplazan de inmediato el volumen del corredor principal. Cuando el sistema fue optimizado por décadas para una ruta, los “planes B” rara vez absorben el shock sin fricciones: no es solo de trazar una ruta distinta en el mapa. Se requiere capacidad instalada, terminales, almacenamiento, seguridad, coordinación operativa y contratos. Por eso, cuando ocurre una disrupción, la red no “migra” como estamos acostumbrados ahora a imaginar con el software: migra como infraestructura pesada de forma lenta y con efectos conexos. El resultado típico es un reemplazo imperfecto: el flujo puede continuar, pero con pérdida de eficiencia, más días de tránsito, mayores costos de trasporte y un alto incremento en costos de riesgo que se traslada al precio final de todos los consumidores. En el caso actual, el mercado ya no estará descontando (o sumando) esa prima, manteniendo presión alcista por el riesgo asociado a Ormuz.

Malaca te enseña el mecanismo, Ormuz lo confirma

La vigencia de lo que escribí hace diez años es, en realidad, la vigencia de la geografía en la economía política global: las cadenas de suministro no son solo contratos. Son rutas y esas rutas pasan por estrechos estratégicos.

Malaca y Ormuz son dos caras de la misma estructura: pasoss angostos en los que transita gran parte del comercio, la energía y la organización productiva del planeta entero. Cuando uno se tensiona por competencia o conflicto armado, la red completa “paga”: precios, inflación, abastecimiento y reacomodo de poder.

La pregunta no es si estos puntos seguirán importando. La pregunta es quién paga cuando se rompen y quién tiene el margen de maniobra para protegerse.

Lecturas recomendadas (para profundizar en Malaca, Ormuz y los chokepoints)

- Robert D. Kaplan, The Revenge of Geography (Random House). Malaca como ejemplo de estrecho “estrecho y vulnerable” en el continuo Indo–Medio Oriente.

- Geoffrey Till, Poder naval: una guía para el siglo XXI (Routledge). Marco de poder marítimo, rutas, seguridad y relevancia estratégica de la geografía naval.

- Daniel Yergin, The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations (Penguin). Relación entre energía, geopolítica y vulnerabilidades del Golfo/Ormuz (comentado en reseñas académicas).

- Tatsuo Masuda, The Straits of Malacca: Critical Sea-Lane Chokepoint (Springer, serie NATO Security through Science). Capítulo especializado sobre Malaca como chokepoint.

- The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, Geopolitics and Maritime Security / Maritime Security in a Time of Renewed Interstate Competition. Menciona explícitamente Malaca y Ormuz como chokepoints prioritarios.